Many students spend hours rereading textbooks, watching lectures, or highlighting notes — yet still struggle to remember what they studied days later.

This is not a motivation problem.

It is a learning strategy problem.

Research in cognitive science consistently shows that passive learning feels productive but produces weak learning outcomes, while active learning feels harder but leads to durable understanding.

This article explains:

- What passive and active learning actually mean

- Why passive learning creates an illusion of mastery

- What research says about effective alternatives

- How to redesign study sessions using evidence-based strategies

What Is Passive Learning?

Passive learning refers to study activities where learners receive information without actively engaging with it.

Common examples include:

- Rereading notes or textbooks

- Watching recorded lectures without interaction

- Highlighting or underlining text

- Copying notes word-for-word

These methods are popular because they feel smooth and familiar. Information flows easily, creating a false sense of understanding.

However, ease of processing is not the same as learning.

What Is Active Learning?

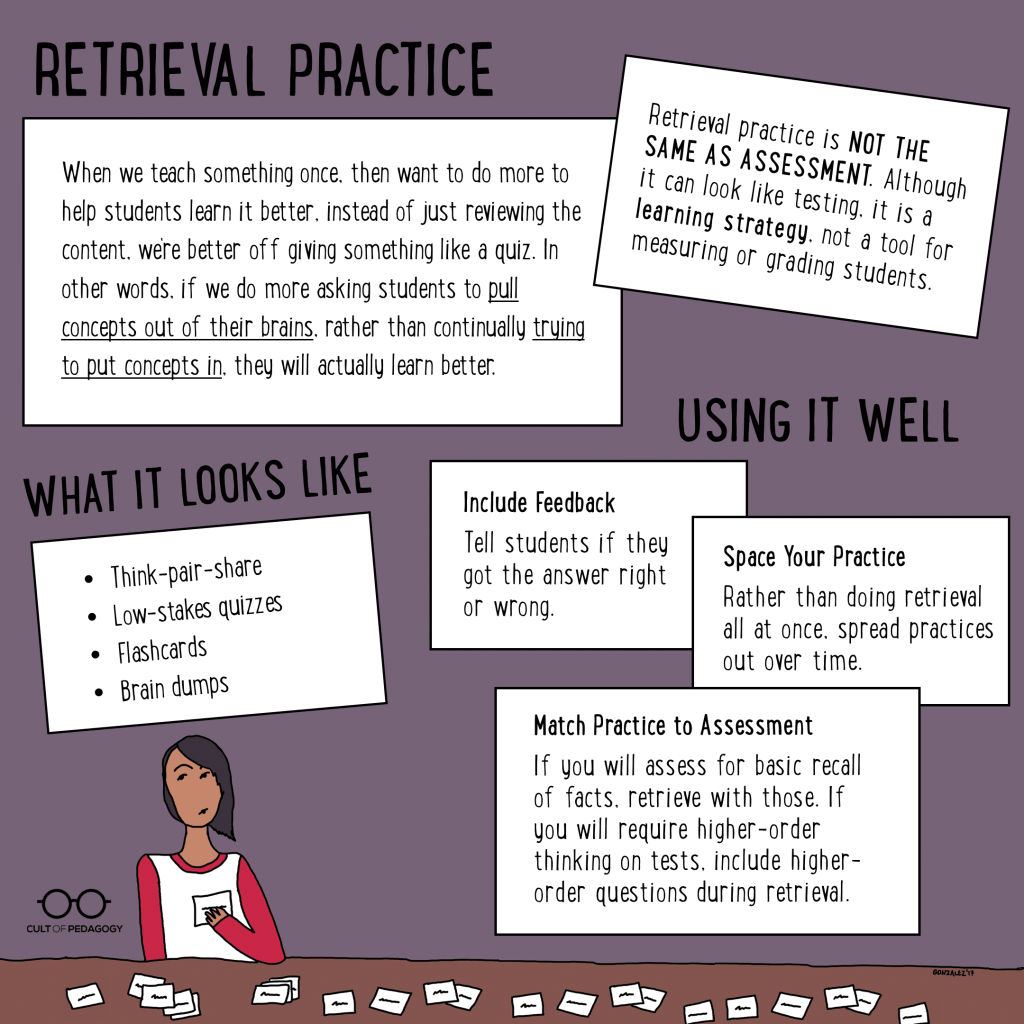

Active learning involves effortful mental processes that require learners to retrieve, manipulate, or apply information.

Examples of active learning include:

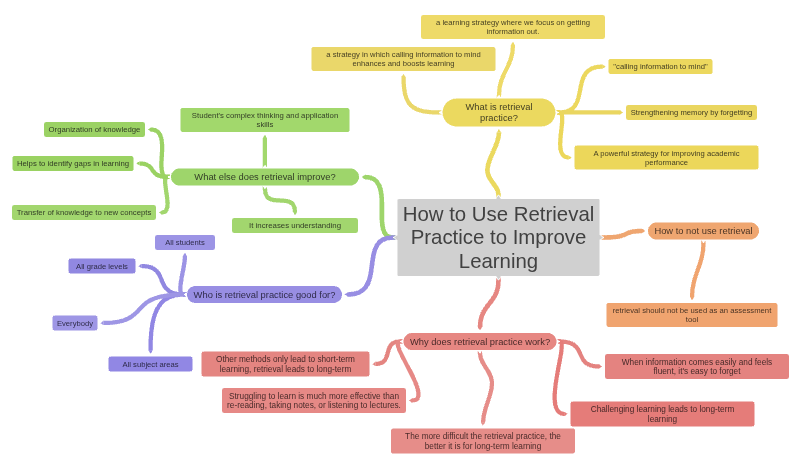

- Self-testing and retrieval practice

- Explaining concepts in your own words

- Teaching the material to someone else

- Solving problems without notes

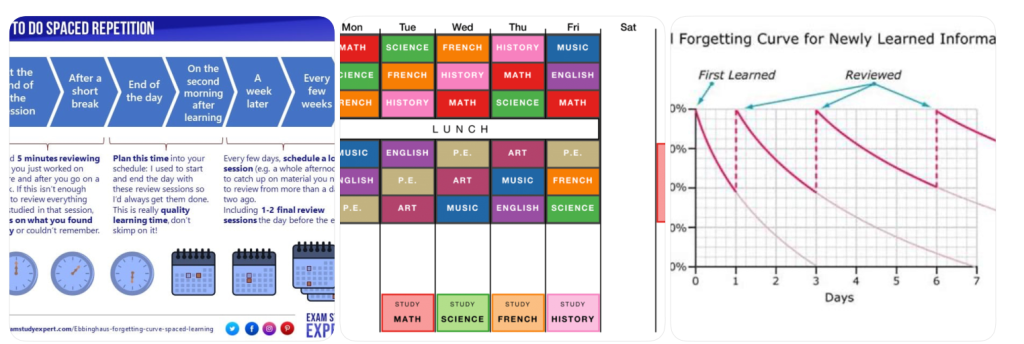

- Spaced repetition over time

Active learning forces the brain to reconstruct knowledge, strengthening memory pathways.

Why Passive Learning Feels Effective (But Isn’t)

Passive learning creates what psychologists call fluency — information feels familiar because it has been seen recently.

But fluency is misleading.

Key research finding

In a classic study by Dunlosky et al. (2013), students rated rereading as highly effective, yet it consistently produced lower long-term retention compared to retrieval-based strategies.

In other words:

Feeling confident ≠ being able to remember later.

The Illusion of Competence

Passive learning leads to an illusion of competence — the belief that you understand material simply because it looks recognizable.

This illusion breaks down when:

- You try to recall information without notes

- You attempt to explain concepts clearly

- You face exam questions that require transfer or application

Active learning exposes gaps early, which feels uncomfortable — but this discomfort is a signal that real learning is happening.

What the Research Says About Active Learning

Multiple large-scale studies support active learning:

- Retrieval practice improves long-term retention more than rereading (Roediger & Karpicke, 2006)

- Spaced practice outperforms cramming across age groups and subjects

- Generative learning (explaining, summarizing, teaching) deepens conceptual understanding

Active strategies work because they increase desirable difficulty — effort that strengthens memory rather than weakens it.

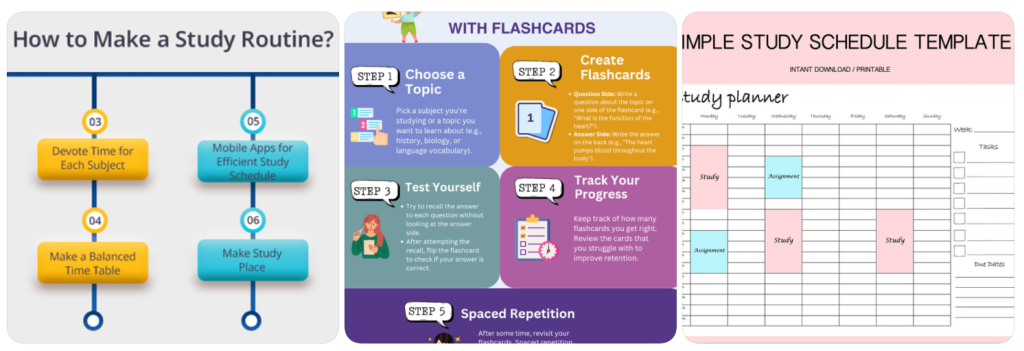

How to Convert Passive Study Into Active Learning

You do not need to study longer. You need to study differently.

Example transformation:

Passive Habit Active Alternative Rereading notes Close notes and write key ideas from memory Watching lectures Pause and predict what comes next Highlighting Create questions from headings Copying notes Explain the topic out loud in simple terms

A Simple Active Learning Study Template

You can structure a 45-minute study session like this:

- 10 minutes – Review goals and key questions

- 20 minutes – Attempt recall without notes

- 10 minutes – Check answers and correct errors

- 5 minutes – Summarize what was difficult

This approach produces far more durable learning than passive review.

Final Takeaway

Passive learning is attractive because it feels easy.

Active learning works because it is effortful.

If your goal is long-term understanding rather than short-term familiarity, the discomfort of active learning is not a weakness — it is the mechanism of learning itself.

References

- Dunlosky, J. et al. (2013). Improving Students’ Learning With Effective Learning Techniques. Psychological Science in the Public Interest.

- Roediger, H. L., & Karpicke, J. D. (2006). Test-enhanced learning. Psychological Science.