How Learning Really Works: A Research-Based Guide to Studying More Effectively

Research in cognitive science and educational psychology has identified clear principles that explain how people learn, retain, and apply knowledge. This article synthesizes well-established research findings to explain how learning works and how students and lifelong learners can study more effectively.

1. Learning Is an Active Cognitive Process, Not Passive Information Intake

A common misconception is that learning happens when information is read, heard, or watched. In reality, learning only occurs when information is actively processed, organized, and integrated into existing knowledge structures.

According to memory research, learning involves three essential stages:

- Encoding – transforming information into meaningful mental representations

- Storage – stabilizing information in long-term memory

- Retrieval – accessing and using stored knowledge

If learners do not actively engage in these processes, information remains short-lived and easily forgotten.

Research source:

Baddeley, A. (1997). Human Memory: Theory and Practice.

2. Working Memory Limits Explain Why Studying Feels Difficult

Human working memory—the mental space used to process information—is extremely limited. Early research by George Miller suggested a capacity of seven items, but later studies refined this to approximately four meaningful units, especially for unfamiliar material.

This limitation explains why:

- Long lectures overload attention

- Dense textbooks feel overwhelming

- Multitasking reduces comprehension

Effective learning strategies must therefore reduce unnecessary mental load and present information in manageable segments.

Research sources:

- Miller, G. A. (1956). The Magical Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two

- Cowan, N. (2001). The Magical Number 4 in Short-Term Memory

3. Cognitive Load Theory: Why More Effort Does Not Always Mean Better Learning

Cognitive Load Theory distinguishes between three types of mental load:

- Intrinsic load – the inherent complexity of the topic

- Extraneous load – unnecessary difficulty caused by poor presentation

- Germane load – mental effort that supports learning

Studies show that learning improves when extraneous load is minimized, allowing learners to focus their mental resources on meaningful understanding.

Examples of excessive extraneous load include:

- Overly complex slides

- Redundant explanations

- Decorative but distracting visuals

Research source:

Sweller, J. (1988). Cognitive Load During Problem Solving. Cognitive Science.

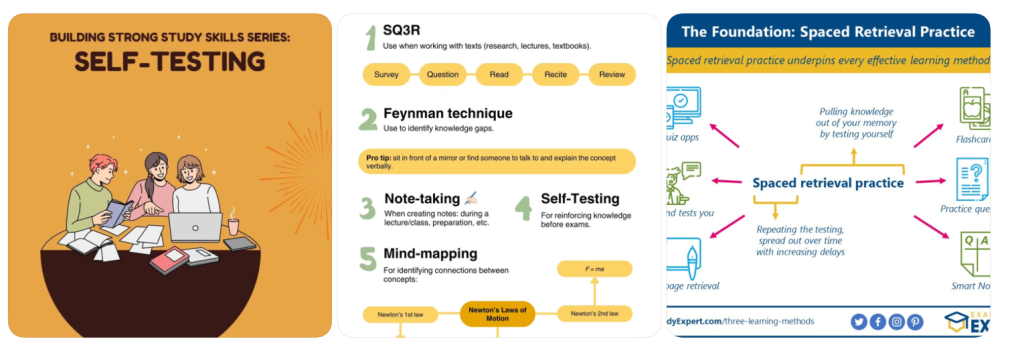

4. Why Retrieval Practice Is More Effective Than Re-Reading

Repeated reading creates familiarity, but familiarity should not be mistaken for learning. Decades of research demonstrate that retrieval practice—actively recalling information—produces stronger and longer-lasting learning.

In controlled experiments, students who practiced retrieval retained significantly more information weeks later than those who simply reviewed the material.

Effective retrieval-based strategies include:

- Self-testing without notes

- Writing summaries from memory

- Explaining concepts aloud

Research sources:

- Roediger, H. L., & Karpicke, J. D. (2006). Test-Enhanced Learning.

- Dunlosky, J. et al. (2013). Improving Students’ Learning With Effective Learning Techniques.

5. Spaced Learning Aligns With How Memory Consolidates

Memory consolidation is a biological process that unfolds over time. Neural changes associated with learning require intervals of rest to stabilize.

Spaced practice takes advantage of this process by distributing study sessions over days or weeks. Meta-analyses covering hundreds of studies consistently show that spaced learning outperforms cramming across age groups and subject areas.

Research source:

Cepeda, N. J. et al. (2006). Distributed Practice in Verbal Recall Tasks. Psychological Bulletin.

6. Prior Knowledge Strongly Influences New Learning

Learning is cumulative. New information is interpreted through existing mental frameworks known as schemas. Learners with stronger prior knowledge acquire new concepts more efficiently and transfer knowledge more effectively.

This explains why identical instruction can produce different learning outcomes across individuals.

Educational implication:

Assessing and activating prior knowledge is essential for effective learning.

Research source:

OECD (2010). The Nature of Learning: Using Research to Inspire Practice.

7. Motivation Affects Persistence, Not Learning Mechanisms

Motivation influences how long learners persist, but it does not replace effective learning strategies. Highly motivated students can still learn inefficiently if they rely on ineffective study methods.

Research shows that instructional design and cognitive alignment matter more than motivation alone.

Research source:

Kirschner, P. A., Sweller, J., & Clark, R. E. (2006). Why Minimal Guidance During Instruction Does Not Work.

8. Practical Implications for Students and Lifelong Learners

Research-based learning environments share several characteristics:

- Information is structured and sequenced

- Cognitive load is carefully managed

- Retrieval is emphasized over repetition

- Learning is spaced over time

- Prior knowledge is explicitly addressed

These principles apply equally to formal education, self-directed learning, and lifelong learning.

Conclusion

Learning is not determined by talent or effort alone. It is governed by cognitive mechanisms that can either support or hinder understanding. Study strategies aligned with these mechanisms consistently outperform those that are not.

By understanding how learning works, students and lifelong learners can make informed decisions that lead to deeper understanding and more durable knowledge.

References (Selected)

- Baddeley, A. (1997). Human Memory. Psychology Press.

- Miller, G. A. (1956). Psychological Review.

- Cowan, N. (2001). Behavioral and Brain Sciences.

- Sweller, J. (1988). Cognitive Science.

- Roediger & Karpicke (2006). Psychological Science.

- Dunlosky et al. (2013). Psychological Science in the Public Interest.

- Cepeda et al. (2006). Psychological Bulletin.

- OECD (2010). The Nature of Learning.