Introduction

Re-reading textbooks and notes is one of the most common study strategies used by students worldwide. It feels productive, familiar, and low-effort. Many learners assume that repeated exposure to information naturally leads to better understanding and memory.

However, decades of research in cognitive psychology suggest otherwise. While re-reading can increase short-term familiarity, it is one of the least effective strategies for long-term learning and knowledge retention.

This article explains why re-reading feels helpful but often fails, what cognitive science reveals about how memory actually works, and which evidence-based strategies are far more effective for durable learning.

Why Re-Reading Feels Effective (But Isn’t)

Re-reading creates a sense of fluency. As the material becomes more familiar, the brain interprets this ease as understanding. Psychologists call this phenomenon the illusion of competence.

In reality:

- Familiarity ≠ mastery

- Recognition ≠ recall

- Ease of reading ≠ ability to retrieve information later

When students re-read, they often confuse recognition (“This looks familiar”) with retrieval (“I can recall this without help”). Exams, problem-solving, and real-world application all depend on retrieval—not recognition.

What Research Says About Re-Reading

A landmark review by Dunlosky et al. (2013), published in Psychological Science in the Public Interest, evaluated ten popular learning strategies. Re-reading ranked low in effectiveness, especially for long-term retention.

Key findings include:

- Re-reading produces minimal gains beyond the first pass

- Benefits are short-lived and fade quickly

- It does not improve transfer of knowledge to new contexts

In contrast, strategies that require active mental effort consistently outperform passive review methods.

The Core Problem: Re-Reading Avoids Retrieval

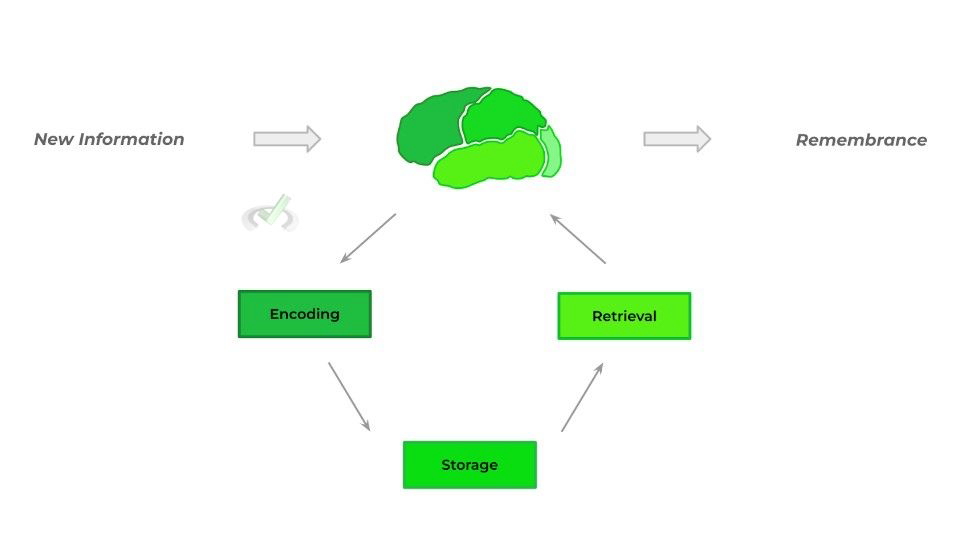

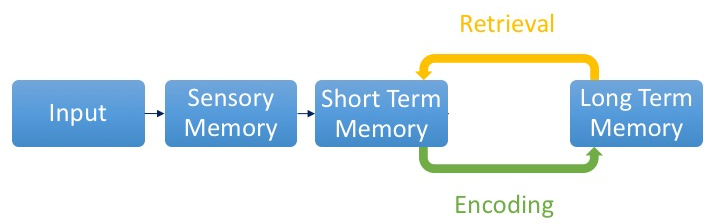

Memory strengthens when it is retrieved, not when it is passively observed.

Re-reading allows learners to:

- Keep answers visible

- Avoid errors

- Avoid mental struggle

But cognitive science shows that struggle is not a bug—it’s a feature. The effort involved in pulling information from memory is what reinforces neural pathways.

This is known as the testing effect: attempting to recall information improves learning more than additional study.

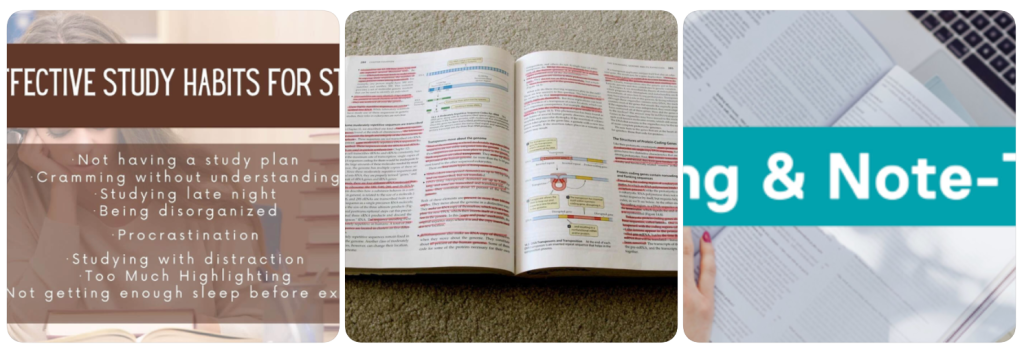

Why Highlighting and Re-Reading Often Go Together

Highlighting frequently accompanies re-reading, yet research shows similar limitations.

Common issues include:

- Over-highlighting without discrimination

- Passive engagement with text

- No requirement to generate or explain ideas

Unless highlighting is followed by active processing (such as summarizing or self-testing), it rarely improves understanding or retention.

Evidence-Based Alternatives That Work Better

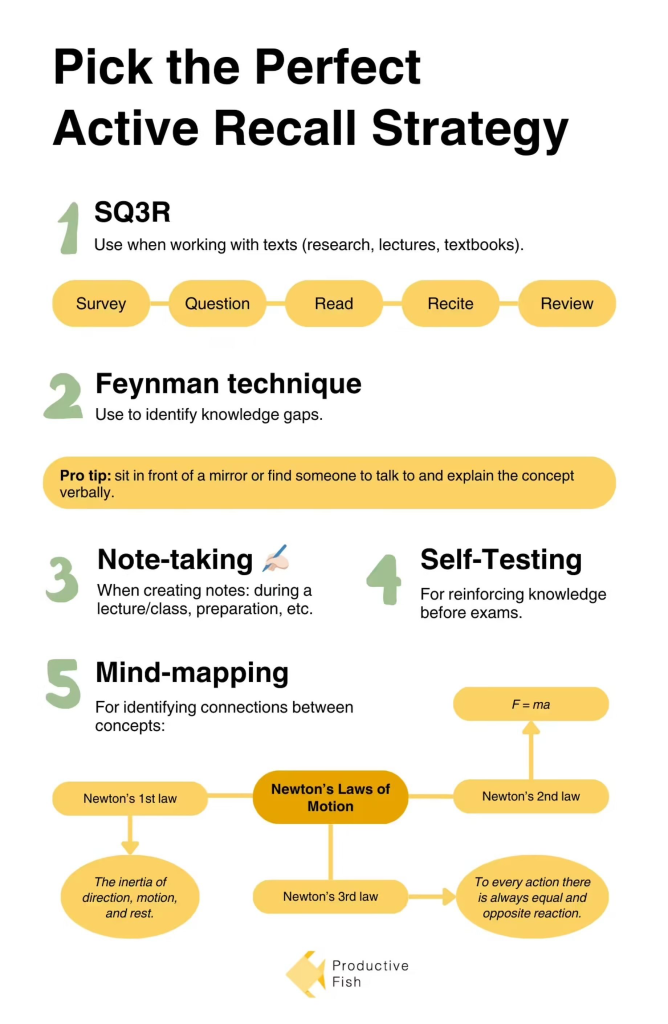

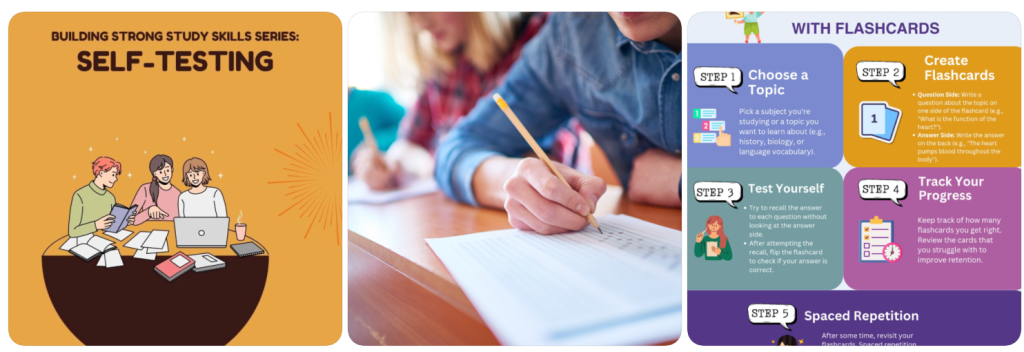

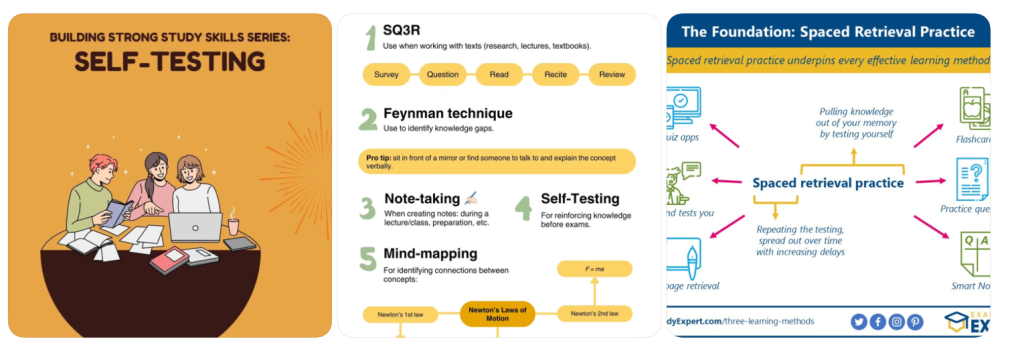

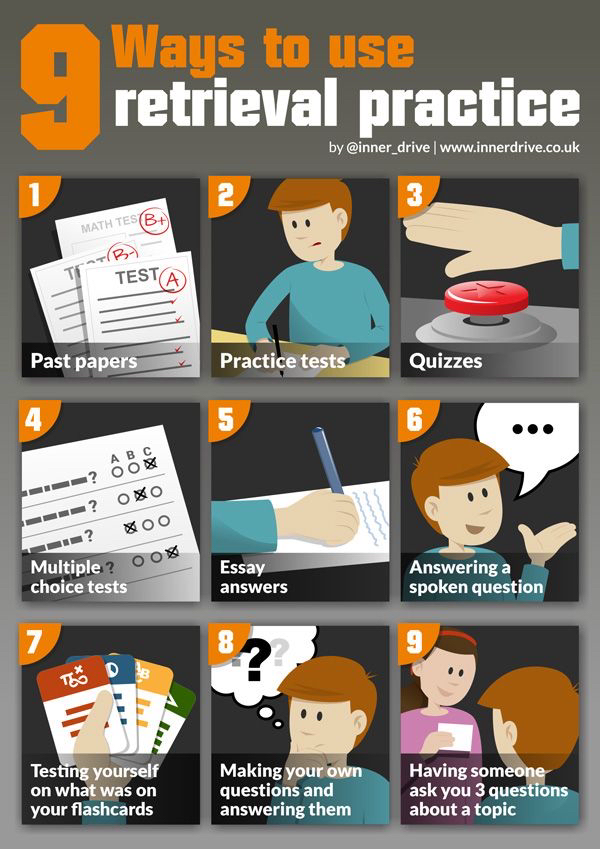

1. Retrieval Practice

Instead of re-reading, learners should regularly ask:

- “What can I remember without looking?”

- “Can I explain this in my own words?”

Effective retrieval methods include:

- Practice questions

- Flashcards

- Writing brief summaries from memory

Even incorrect attempts strengthen learning by revealing gaps.

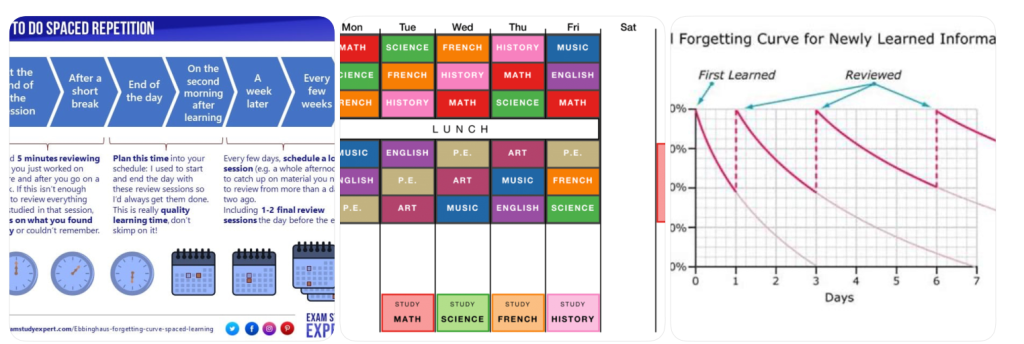

2. Spaced Practice

Spreading study sessions over time dramatically improves retention compared to massed study (cramming or repeated re-reading).

Spaced practice works because it:

- Forces repeated retrieval

- Introduces desirable difficulty

- Prevents overconfidence

This approach aligns with how memory consolidates over time.

3. Elaboration and Explanation

Learners retain more when they actively connect new information to existing knowledge.

Examples include:

- Explaining concepts as if teaching someone else

- Creating analogies

- Asking “why” and “how” questions

These strategies deepen understanding and improve transfer to new problems.

When Re-Reading Can Still Be Useful

Re-reading is not entirely useless. It can help when:

- Introducing completely new material

- Clarifying confusing sections

- Reviewing structure before active practice

However, it should serve as a preparation step, not the primary study strategy.

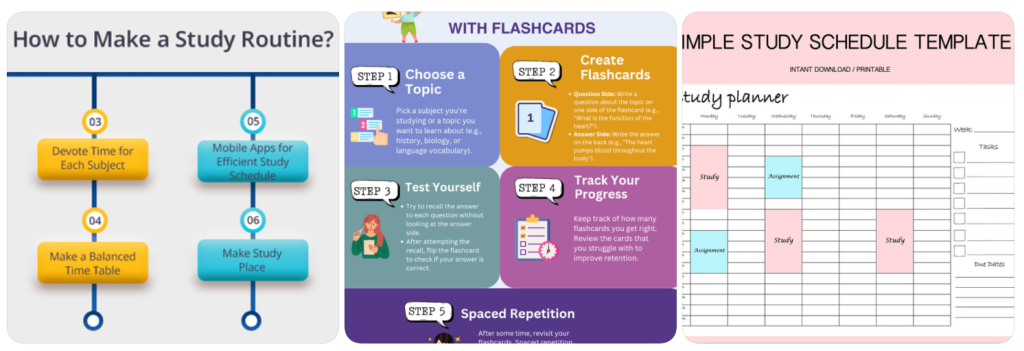

Practical Study Framework (Research-Aligned)

A more effective approach looks like this:

- Initial exposure – Read once for comprehension

- Active recall – Close the material and retrieve key ideas

- Feedback – Check accuracy and fill gaps

- Spacing – Revisit after time has passed

This cycle aligns with how learning actually occurs.

Conclusion

Re-reading feels productive because it is easy and familiar—but learning is not built on ease. Cognitive science consistently shows that active, effortful strategies outperform passive review for long-term retention and understanding.

Students who replace excessive re-reading with retrieval practice, spacing, and explanation learn more efficiently and retain knowledge longer.

Effective learning is not about spending more time—it’s about using strategies that work with the brain, not against it.