Introduction

Many students rely on cramming — studying intensively right before an exam — because it seems efficient. In the short term, this approach can produce quick results, especially when tests focus on recent material.

However, decades of research in cognitive psychology show that cramming is one of the least effective ways to achieve long-term learning. While it may boost short-term performance, it often fails to support durable memory and knowledge transfer.

This article examines why cramming feels effective, how human memory actually works, and what learning science reveals about more effective alternatives.

What Is Cramming?

Cramming refers to massed study, where large amounts of information are reviewed in a short period of time, typically right before an exam.

Common signs of cramming include:

- Studying for many hours in one session

- Reviewing material only once

- Little or no review after the exam

- Prioritizing speed over understanding

While cramming may feel productive, its effects on memory are largely temporary.

Why Cramming Feels Effective

Cramming works primarily because of short-term memory activation. When information is reviewed repeatedly in a brief window, it remains accessible for a short time.

This creates two powerful illusions:

- Fluency illusion – Material feels familiar, leading learners to believe it is well understood.

- Performance illusion – Immediate recall is mistaken for long-term learning.

Research shows that performance during study is not a reliable indicator of future retention.

📚 Source:

Soderstrom, N. C., & Bjork, R. A. (2015). Learning Versus Performance. Psychological Science.

How Memory Actually Works

Human memory depends on encoding, consolidation, and retrieval.

- Encoding: Initial exposure to information

- Consolidation: Stabilization of memory over time

- Retrieval: Accessing stored information later

Cramming heavily emphasizes encoding but leaves little time for consolidation. Without sufficient spacing and retrieval, memories remain fragile and are easily forgotten.

The Spacing Effect: Why Time Matters

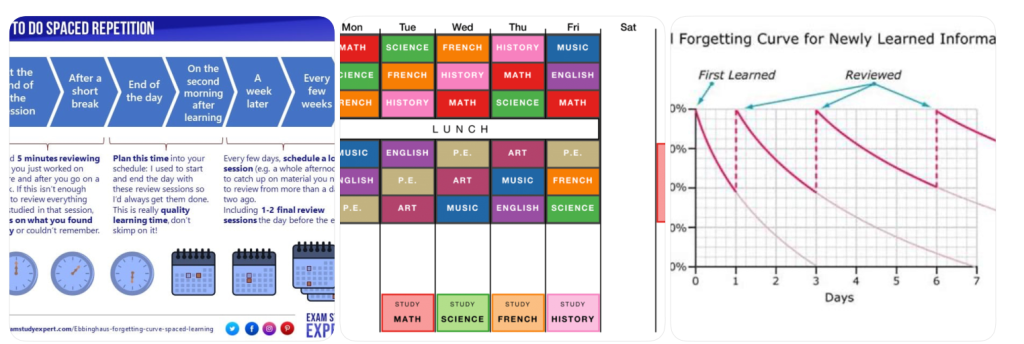

One of the most robust findings in learning science is the spacing effect.

Research consistently shows that:

- Information studied over spaced sessions is retained longer

- Total study time can be the same, yet outcomes differ dramatically

- Forgetting between sessions actually strengthens learning

📚 Source:

Cepeda, N. J. et al. (2009). Spacing Effects in Learning. Psychological Science.

Cramming eliminates spacing entirely, which explains why knowledge gained through cramming fades quickly.

Cramming vs Spaced Learning: A Comparison

| Aspect | Cramming | Spaced Learning |

|---|---|---|

| Study timing | One session | Multiple sessions |

| Retention | Short-term | Long-term |

| Cognitive effort | Low to moderate | Moderate |

| Forgetting rate | High | Low |

| Research support | ❌ | ✅ |

Why Cramming Fails Under Pressure

Under stress — such as exams or real-world application — learners rely on retrieval strength, not familiarity.

Because crammed information has weak retrieval pathways:

- Recall breaks down under pressure

- Knowledge cannot be transferred to new contexts

- Learning feels unstable and unreliable

This explains why students often “blank out” despite extensive last-minute study.

When Cramming Might Appear to Work

It is important to acknowledge that cramming can produce short-term performance gains, particularly when:

- Exams focus on recognition rather than recall

- Material will not be needed again

- Time constraints are extreme

However, research suggests that these gains come at the cost of rapid forgetting and limited understanding.

Evidence-Based Alternatives to Cramming

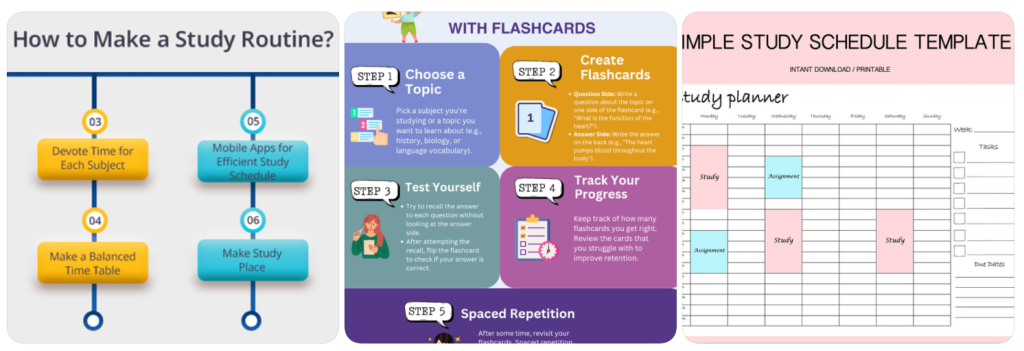

Learning science identifies several strategies that consistently outperform cramming:

1. Spaced Practice

Review material across days or weeks.

2. Active Recall

Test yourself without notes to strengthen retrieval.

3. Interleaving

Mix related topics instead of studying one topic at a time.

4. Reflection

Identify mistakes and misunderstandings during review.

These strategies may feel slower but lead to more durable learning.

Final Thoughts

Cramming persists because it feels efficient, not because it is effective. Research in cognitive science clearly shows that long-term learning depends on spacing, retrieval, and time.

By shifting away from last-minute study and toward evidence-based learning strategies, students can improve not only exam performance but also long-term understanding and knowledge retention.

References

- Soderstrom, N. C., & Bjork, R. A. (2015). Psychological Science

- Cepeda, N. J. et al. (2009). Psychological Science

- Bjork, R. A. (1994). Memory and Metamemory Considerations